The Excess of Fresh Figs — Para o meu avô Julio que ama figos

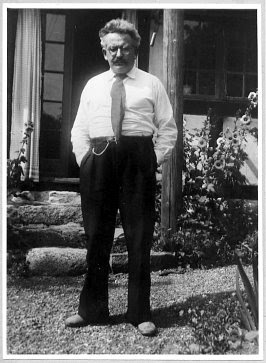

"Fresh Figs" by Walter Benjamin

No one who has never eaten a food to excess has ever really experienced it, or fully exposed himself to it. Unless you do this, you at best enjoy it, but never come to lust after it, or make the acquaintance of that diversion from the straight and narrow road of the appetite which leads to the primeval forest of greed. For in gluttony two things coincide: the boundlessness of desire and the uniformity of the food that sates it.

Gourmandizing means above all else to devour one thing to the last crumb.

There is no doubt that it enters more deeply into what you eat than mere enjoyment. For example, when you bite into mortadella as if it were bread, or bury your face in a melon as if it were a pillow, or gorge yourself on caviar out of crackling paper, or, when confronted with the sight of a round Edam cheese, find that the existence of every other food simply vanishes from your mind.

There is no doubt that it enters more deeply into what you eat than mere enjoyment. For example, when you bite into mortadella as if it were bread, or bury your face in a melon as if it were a pillow, or gorge yourself on caviar out of crackling paper, or, when confronted with the sight of a round Edam cheese, find that the existence of every other food simply vanishes from your mind.

—How did I first learn all this?

It happened just before I had to make a very difficult decision. A letter had to be posted or torn up. I had carried it around in my pocket for two days, but had not given it a thought for some hours. I then took the noisy narrow-gauge railway up to Secondigliano through the sun-parched landscape. The village lay in still solemnity in the weekday peace and quiet. The only traces of the excitement of the previous Sunday were the poles on which Catherine wheels and rockets had been ignited. Now they stood there bare. Some of them still displayed a sign halfway up with the figure of a saint from Naples or an animal. Women sat in the open barns husking corn.

I was walking along in a daze, when I noticed a cart with figs standing in the shade. It was sheer idleness that made me go up to them, sheer extravagance that I bought half a pound for a few soldi. The woman gave me a generous measure. But when the black, blue, bright green, violet, and brown fruit lay in the bowl of the scales, it turned out that she had no paper to wrap them in. The housewives of Secondigliano bring their baskets with them, and she was unprepared for globetrotters. For my part, I was ashamed to abandon the fruit.

So I left her with figs stuffed in my trouser pockets and in my jacket, figs in both of my outstretched hands, and figs in my mouth. I couldn’t stop eating them and was forced to get rid of the mass of plump fruits as quickly as possible. But that could not be described as eating; it was more like a bath, so powerful was the smell of resin that penetrated all my belongings, clung to my hands and impregnated the air through which I carried my burden. And then, after satiety and revulsion – the final bends in the path – had been surmounted, came the ultimate mountain peak of taste. A vista over an unsuspected landscape fo the palate spread out before my eyes – an insipid, undifferentiated, greenish flood of greed that could distinguish nothing but the stringy, fibrous waves of the flesh of the open fruit, the utter transformation of enjoyment into habit, of habit into vice.

A hatred of those figs welled up inside me; I was desperate to finish them, to liberate myself, to rid myself of all this overripe, bursting fruit. I ate to destroy it. Biting had rediscovered its most ancient purpose. When I pulled the last fig from the depths of my pocket, the letter was stuck to it. Its fate was sealed; it, too, had to succumb to the great purification. I took it and tore it into a thousand pieces.